第3章 Prologue

Long before there was a digital media and education company or a radical self-love movement with hundreds of thousands of followers on our website and social media pages, before anyone cared to write about us in newsprint or interview me on television, before people began to send me photos of their bodies with my words etched in ink on their backs, forearms, and shoulders (which never stops being awesome and weird), there was a word…well, words. Those words were "your body is not an apology." It was the summer of 2010, in a hotel room in Knoxville, Tennessee. My team and I were preparing for evening bouts in competition at the Southern Fried Poetry Slam. Slam is competitive performance poetry. Teams and individuals get three minutes onstage to share what is often deeply intimate, personal, and political poetry, at which point five randomly selected judges from the audience score their poems on a scale from 0.0 to 10.0. It's a raucous game that takes the high art of poetry and brings it to the masses in bars, clubs, coffee shops, and National Poetry Slam Championship Tournaments around the country. Poetry slam is as ridiculous as it is beautiful; it is everything gauche and glorious about the power of the word. The slam is a place where the misfit and the marginalized (and the self-absorbed) have center stage and the rapt ears of an audience, if only for three minutes.

It was on a hotel bed in this city, preparing for this odd game, that I uttered the words "your body is not an apology" for the first time. My team was a kaleidoscope of bodies and identities. We were a microcosm of a world I would like to live in. We were Black, White, Southeast Asian. We are able bodied and disabled. We were gay, straight, bi, and queer. What we brought to Knoxville that year were the stories of living in our bodies in all their complex tapestries. We were complicated and honest with each other, and this is how I wound up in a conversation with my teammate Natasha, an early-thirtysomething living with cerebral palsy and fearful she might be pregnant. Natasha told me how her potential pregnancy was most assuredly by a guy who was just an occasional fling. All of life was up in the air for Natasha, but she was abundantly clear that she had no desire to have a baby and not by this person. One of my many career iterations of the past was as a sexual-health and public-health service provider. This background made me notorious for asking people about their safer-sex practices, handing out condoms, and offering sexual-health harm-reduction strategies. Instinctually, I asked Natasha why she had chosen not to use a condom with this casual sexual partner with whom she had no interest in procreating. Neither Natasha nor I knew that my honest question and her honest answer would be the catalyst for a movement. Natasha told me her truth: "My disability makes sex hard already, with positioning and stuff. I just didn't feel like it was okay to make a big deal about using condoms."

When we hear someone's truth and it strikes some deep part of our humanity, our own hidden shames, it can be easy to recoil into silence. We struggle to hold the truths of others because we have so rarely had the experience of having our own truths held. Social researcher and expert on vulnerability and shame Brené Brown says, "If we can share our story with someone who responds with empathy and understanding, shame can't survive."[1] I understood the truth Natasha was sharing. Her words pricked some painful underbelly of knowing in my own body. My entire being rang in resonance. I was transported to all the times I had given away my own body in penance. A reel of memories scrolled through my mind of all the ways I told the world I was sorry for having this wrong, bad body. It was from this deep cave of mutual vulnerability that the words spilled from me, "Natasha, your body is not an apology. It is not something you give to someone to say, 'Sorry for my disability.' " She began to weep, and for a few minutes I just held my maybe-pregnant friend as she contemplated the fullness of what those words meant for her life and her body. There are times when our unflinching honesty, vulnerability, and empathy will create a transformative portal, an opening to a completely new way of living. Such a portal was created between Natasha and me that summer evening in Tennessee, because as the words escaped my lips some part of them remained stuck inside me. The words I said to Natasha in that hotel room were as much for me as they were for her. I was also telling myself, "Sonya, your body is not an apology."

At every turn, for days after my conversation with Natasha, the words returned to me like some sort of cosmic boomerang. They kept echoing off the walls of all my hidden hurts. Every time I uttered a disparaging word about my dimpled thighs I'd hear, "Your body is not an apology, Sonya." Each time I marked some erroneous statement with "My bad. I'm so stupid," my own inner voice would retort, "Your body is not an apology." Whenever my critical eye focused laser-like on some perceived imperfection of my own or some other human's being, the words would arrive like a well-trained butler to remind me, "Hey, the body is not an apology." My poet self knew that the words were demanding to be more than a passing conversation with a friend. They wanted more than my own self-flagellation. The words always had their own plans. Me, I was just a vessel.

I recently listened to famed author and spiritual teacher Marianne Williamson share a talk on relationships. In it, she described the principle of natural intelligence. She posited, "An acorn does not have to say, 'I intend to become an oak tree.' Natural intelligence intends that every living thing become the highest form of itself and designs us accordingly."[2] In a single sentence, all in me that felt nameless was named. We have a dictionary full of terms describing our interpretation of natural intelligence. We sometimes call it purpose; other times, destiny. Although I agree with the spirit of those terms, I believe they fail to encapsulate the fullness ofwhat Marianne Williamson's acorn example illustrates. Both purpose and destiny allude to a place we might, with enough effort, someday arrive. We belabor ourselves with all the things we must do to fulfill our purpose or live out our destiny. Contrary to purpose, natural intelligence does not require we do anything to achieve it. Natural intelligence imbues us with all we need at this exact moment to manifest the highest form of ourselves, and we don't have to figure out how to get it. We arrived on this planet with this source material already present. I am by no means implying that the work you may have done up to this point has been useless. To the contrary, I applaud whatever labor you have undertaken that has gotten you this far. Survival is damn hard. Each of us has traversed a gauntlet of traumas, shames, and fears to be where we are today, wherever that is. Each day we wake to a planet full of social, political, and economic obstructions that siphon our energy and diminish our sense of self. Consequently, tapping into this natural intelligence often feels nearly impossible. Humans unfortunately make being human exceptionally hard for each other, but I assure you, the work we have done or will do is not about acquiring some way of being that we currently lack. The work is to crumble the barriers of injustice and shame leveled against us so that we might access what we have always been, because we will, if unobstructed, inevitably grow into the purpose for which we were created: our own unique version of that oak tree.

I have my own name for natural intelligence. I call it radical self-love. Radical self-love was the force that cannoned the words "your body is not an apology" out of my mouth, directed toward a friend but ultimately barreling into my own chest and then into the hearts of hundreds of thousands of people around the world. Evangelizing radical self-love as the transformative foundation of how we make peace with our bodies, make peace with the bodies of others, and ultimately change the world is my highest calling. Coincidence after seeming coincidence has made that much evident. I don't know what your highest calling is. It's possible you don't quite know either. That is perfect. At this very second, a trembling acorn is plummeting from a branch, clueless as to why. It doesn't need to know why to fulfill its calling; it just needs us to get out of its way. Radical self-love is an engine inside you driving you to make your calling manifest. It is the exhaustion you feel every time the whispers of self-loathing, body shame, and doubt skulk through your brain. It is the contrary impulse that made you open this book, an action driven by a force so much larger than the voice of doubt and yet sometimes so much more difficult to hear.

Radical self-love is not a destination you are trying to get to; it is who you already are, and it is already working tirelessly to guide your life. The question is how can you listen to it more distinctly, more often? Even over the blaring of constant body shame? How can you allow it to change your relationship with your body and your world? And how can that change ripple throughout the entire planet? At the organization I founded, The Body Is Not an Apology, we are not saying anything new (see www.TheBodyIsNotAnApology.com). We are, however, connecting some straggling dots we believe others may have missed along the way. We know that the answer has always been love. The question is how do we stop forgetting the answer so we can get on with living our highest, most radically unapologetic lives. This book is my most sincere effort to help us all answer that.

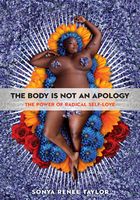

The Body Is Not an Apology